How can we make science more connected to society and the environment that embraces it?

AMB LA CO-AUTORIA DE:

AMB LA CO-AUTORIA DE:

Who do we research for and why? Although these questions may seem easy to answer, they open the door to profound reflections and multiple implications. At scientific institutions, we investigate not only to satisfy our curiosity about how the world works, but also to respond to the great challenges of our time, generate useful and transformative knowledge, improve existing knowledge, and advance our understanding of our environment. We are driven by a passion for discovery, a commitment to society, a responsibility to preserve the planet, and a desire to contribute to a more just and sustainable future.

In this context, scientific research - the knowledge, tools, and practices that derive from it - has society and its needs, both present and future, as its core.

At CREAF, we strive to ensure that our science inspires new ways of living and coexisting, guaranteeing a habitable planet for both nature and people. We firmly believe in excellent and relevant science that can generate knowledge to help us understand nature, anticipate threats, and provide solutions to environmental and climate challenges. This will improve the health of ecosystems and our relationship with them.

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

Although it is often not obvious to us, we are part of nature. Humans play a pivotal role in ecosystems, capable of either positive or negative transformation. Therefore, it is particularly important for our field of research to include non-academic individuals and institutions in our research processes.

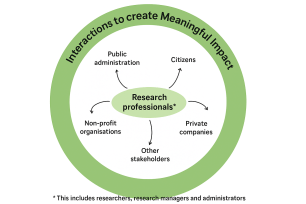

The relationship between society and science is built through interactions between researchers, research institutions, citizens, and various civil organisations, such as entities, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and public administrations. It is through these connections that research can have an impact beyond the academic sphere, transforming practices, informing policies and contributing to the resolution of collective challenges. In this new Impact Corner article, we explore this vital connection, how to put it into practice, and its potential.

The importance of social agents in generating impact

The importance of social agents in generating impact

For research to be truly relevant and beneficial to society, it is not enough for scientific knowledge to be generated; it must also be shared, understood and used by people, institutions, organisations, companies and administrations beyond the academic sphere. This requires more than just communicating the results; it demands the involvement of society from the outset of projects, throughout their development, and after they have been completed. To achieve this, spaces for collaboration and trust are needed where all parties — scientists, citizens, entities and professionals — can learn from each other, ask questions, imagine solutions and contribute their knowledge and experience (In this article, we discuss this path to impact).

Diagram of interactions between research professionals and various social agents to create a significant impact.

However, despite all these efforts, it is important to note that research groups cannot directly generate or control impact. While we can facilitate impact through quality interactions, active listening, collaboration and meaningful knowledge sharing, whether research is adopted and applied to generate concrete change also depends on the social, political and institutional contexts in which it occurs. In this sense, impact is valued by those who receive it. It is not an inherent property of knowledge, but rather the consequence of a collective, relational process in which science takes on meaning through constant dialogue with society.

It is key to know who is interested in what we do (and the level of their contribution)

It is key to know who is interested in what we do (and the level of their contribution)

When we translate this idealised discourse on interactions, benefits and collaborations with society into practice, we often realise that we are not entirely clear about who these potential collaborators are or what their involvement in the research framework may be. This is why it is important to carry out a mapping exercise to identify who may be involved in a specific piece of research and the extent to which they may be connected to and influence it.

To carry out this exercise, it is important to consider both direct and indirect beneficiaries. One approach is to categorise them according to their potential level of involvement and capacity for action within the project, ranging from the most active to the most passive participants. J. Bayley, in his book Creating Meaningful Impact: The Essential Guide to Developing an Impact-Literate Mindset, categorises them according to the energy we should invest, the influence they can have, and their level of interest (and to avoid frustration in advance):

- Who can use it and therefore implement and participate directly in the solution and benefit from it . They have the necessary resources and skills, so we should dedicate as much energy as possible to them.

- Who can provide access and act as a bridge between ideas or solutions and the people who can use them. They are often key to reaching the right people or entities.

- Who can act as a spokesperson and advocate to help convince and mobilise people by promoting and spreading the message.

- Those who listen and participate passively, have no real commitment to the message and do not act.

- Those who pass by and have no real interest and pretend to listen, but do not. In some cases, their attitude can slow down or confuse the process. This is especially true if we do not detect this in time and devote too much effort and time to them.

Active working group in the Bewater project Workshop.

This analysis helps to prioritise efforts and establish meaningful relationships. It also encourages recognition that research can have unintended consequences for certain groups and highlights the importance of incorporating an ethical perspective to minimise these consequences.

Equally important is reviewing one's own biases and expanding the scope of stakeholders to include future generations, vulnerable groups and non-human beneficiaries. These often-invisible groups can be crucial in identifying and implementing the solutions that science proposes, so it is important to consider them if we want research to be truly inclusive and transformative.

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

The transformative power of knowledge mobilisation

The transformative power of knowledge mobilisation

An interesting concept in these interactions that is gaining international attention is knowledge mobilisation (KMb). Unlike traditional knowledge transfer, KMb emphasises co-creation, adaptation and collaboration between social and public organisations and researchers. It is not just a matter of 'sharing' knowledge, but of making it useful and relevant to all parties, so they feel they are actively contributing to science while enriching it — often without fully realising it.

Although the concept is relatively recent, the practices that promote it have a much longer history. Research with social implications is nothing new; we have been carrying out research initiatives that connect scientific work with the needs and perspectives of society for decades. The approaches taken differ depending on the disciplines and contexts involved. This has materialised in the form of various collaborations. Examples include participatory workshops, action research with local communities or diverse stakeholders, living labs, and mixed working groups with public administrations for the co-design and evaluation of public policies, as well as citizen science projects involving people in research. These methods of knowledge generation produce more applicable and contextualised results, while also strengthening the relationship between science and society.

This is why we see this type of research as a shared process: researchers facilitate change rather than acting solely as ‘producers’ of knowledge, and society benefits from and participates in this process. Impact is generated not only from the results of the research, but also from this process of exchange and mutual enrichment throughout the research process.

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED IN

This is why we see this type of research as a shared process: researchers facilitate change rather than acting solely as ‘producers’ of knowledge, and society benefits from and participates in this process. Impact is generated not only from the results of the research, but also from this process of exchange and mutual enrichment throughout the research process.

When we involve people in research, we generate dialogue and build shared knowledge, giving rise to a different way of doing science. This new approach is capable of influencing the practices, values and ways of thinking of citizens from the beginning. This approach is profoundly transformative for both society and researchers, and is not an idealistic or pretentious view of science's role. In the context of today's major challenges, complex issues demand interdisciplinary and collaborative solutions that incorporate the perspectives of a wide range of stakeholders, not just academics, to co-create more comprehensive, relevant, and robust responses.

Finally, we would like to invite you to consider the following reflective questions:

- Who might need or benefit from your research?

- Does the proposed solution truly address an existing need, and can it be implemented in the intended context?

- Have we consulted with the various stakeholders to understand the problems they have identified and how they think they should be addressed?

- Have we considered the relevance of the research in terms of advancing knowledge and its potential benefits to society?

To Know more...

3i framework: Stakeholder Planning exercise (Fast Track Impact)

Knowledge mobilisation Toolkit (Ontario Centre for excellence for child and youth mental Health)

KMb101: Introduction to Knowledge Mobilization – Research Impact Canada